[Image: Aert van der Neer, “Moonlit Landscape with Bridge,” 1648/50 (?), courtesy National Gallery of Art, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, public domain.]

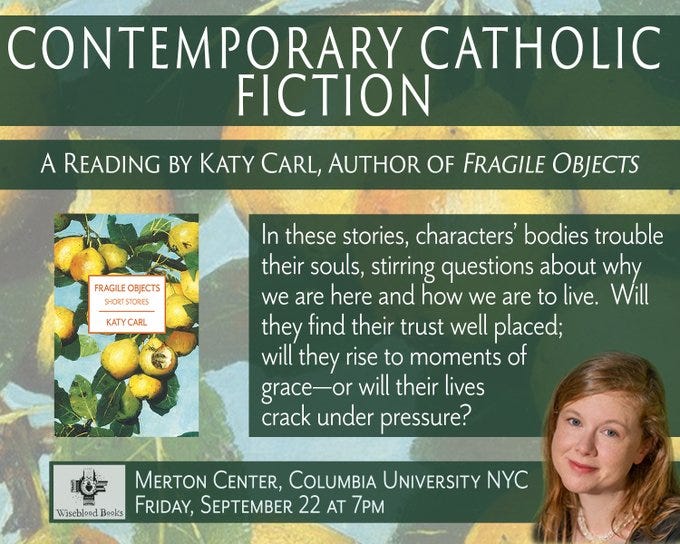

Heads up! NYC-area or -adjacent readers: I’d love to see you this Friday, 9/22 at 7 p.m., at Columbia University’s Merton Center, which is generously hosting me for a reading from Fragile Objects. If I were any more thrilled I’d have to be two people to contain it. Please join us if you can.

Now to the main question. It has been preoccupying me for a while, but more consciously since my recent conversation with fellow fiction writer Seth Wieck of In Solitude, For Company.

In that exchange, Seth asked:

Why [focus on] contemplation instead of enchantment? How are those two things related, and how might contemplation, in your mind, be a better way of thinking about reality?

An opening caveat: I don’t mean to speak against the concept of enchantment as it shows up either in conversations about art or conversations about the natural world, culture, worship, and the closely nested relationships among all of these. This is why I added [focus on] in brackets: That context, that balance, seemed clear in the original interview, but it’d be easy to miss when pulled into a new window.

So the whole project of re-enchanting experience, of falling back in love with fresh clear ways of seeing the world, ways we tend to attribute to previous civilizations though we have little way of knowing what their experience truly was, ways to which children might seem to have perennial access1 but for which adults have to labor—all this has my sympathy. All this is perfectly compatible with, even consciously contained within, the contemplative realist project. So, nothing that I say about preferring a contemplative mode of seeing should be taken as devaluing an enchanted mode.

That said, what floated to the top of mind in response to Seth’s question surprised even me. I hadn’t known I held it so closely. Yet as it turns out, I’ve long been working with the desire to get down into layers of reality where I think art-as-enchantment doesn’t always necessarily take us, though it can.

Now, I can promptly supply many counterexamples of “enchanted” work, poem-as-charm or carmen—my favorite is Dana Gioia’s “Haunted”—which does take us to those layers without ever breaking the surface tension of flawless illusion. How to get a parallel effect in prose fiction occupies me tremendously. But the deeper substance of the matter seems to me to lead to another question: Once you have figured out how to get the effect, what do you do with it? Where do you take us?

Aesthetic enchantment, because it suspends and engages the attention fruitfully, can be an aid to contemplation rather than an obstacle. This suspension, this engagement, has a relationship to aesthetic enstrangement or defamiliarization. This fancy term just means the rendering of the act of perception “longer and more laborious” so as to make it, ultimately, clearer. By enstrangement our vision is refreshed, as we are made to see something familiar as though it were new. This kind of enchantment, if we want to call it that, is related to the “fast that is pleasing to the eyes.”

But there also exist—and you’ve likely tasted some of them—more bitter or sour flavors of enchantment, which maybe aren’t actually aesthetic “enchantment” at all: which aren’t really so much interested in perpetuating this act of shared attention as it wants to be paid attention to by whatever means are necessary to arrest the reader’s attention. I don’t mean shock value or cultivated ugliness, both of which tend to get a bad name in circles occupied with “truth, goodness, and beauty” but both of which can be consciously and responsibly included in a work that achieves its total effect by a kind of formal completeness, a correspondence with the known world. I mean something else, a sort of warped or spoiled quality, a bruising in the work itself which is transferred to the receiver of the work, a kind of terrifying scrabbling clutching at your arm that it does.

I don’t know how to put language on this exactly, which is why I’m interested in it. I want to call this spoiled or false craft “conjuring,” which is the name it goes by in the interview, though we could think of others. Maybe it’s wrong to think of it as enchantment properly speaking, though the associative leap that led me there should be clear enough. I’m just working something out here, so I’m open to putting pressure on this expression and seeing where it may take us.

But if you’ll take a moment to investigate your own experience as a reader, you’ll automatically realize why we need to explore this issue of where an aesthetic bent leads us and how it is used, to what ends. You’ll have had the experience of giving up on a book or a work of art because, rather than engaging or intriguing or inviting you to make meaning in collaboration with it, it felt like it wanted to ensnare you. Compel you. Something about it felt malevolent. Vampiric. Work like this we should run, not walk, away from.

But that’s not the only, or even the most common, way in which craftiness can go sideways. When I get disaffected or exhausted with works of fiction—extend the analogy for other kinds of art—I find that it’s sometimes because their (often highly competent) creators have figured out how to get my attention but seem not to have figured out what they want with it. In Wallace’s terms, they have discovered “how but not why” to tell a story. This is as much as to say that whatever else they can do on the page, they haven’t figured out how to contemplate, even on a natural level. They don’t seem to know why we’re looking at what we’re looking at, or looking for, together.

I’ve been in this position of the storyteller who can’t answer (or rather, whose invented narrator can’t answer) the question: Why are you telling me this? The only useful answers I’ve ever found have come through entering more fully into the act of contemplation, even on the natural level. Through looking more closely. Through paying better attention. Through trying harder to see that which tries to resist being seen, which seeks to hide, which fears the light.

To capture someone else’s attention seems to be a fairly simple matter (far simpler, sometimes, than to catch and control our own). Humans are hardwired for fascination with each other, and this is an easy state of affairs to exploit. But to hold and direct someone’s attention to good purpose implies a position of trust, therefore of responsibility. It seems to me that we have to work toward being more deserving of this trust, which can only ever really have its highest value if it is freely bestowed as gift.

Maybe all I’m saying is that to my mind enchantment is a desirable readerly state; contemplation, a desirable writerly one. But why should that matter? Well, why ever in our day should we need to sharpen our senses for story’s shapes and storytellers’ intentions, whether these are apparent or buried? To be aware of, not whether, but when, we are being fed broken facts and partial truths bent to fit facile or oversimplified narratives? To be aware of ourselves, too, as storytellers—to ourselves, to others, and in our various public and private roles—and to question, not whether, but when we are in possession only of broken facts and partial truths?

Why should we? I’ll let you muse on that one.

We say this, but I wonder sometimes how true it really is. As a parent I have a privileged window on how often childhood can be a state of not seeing. And as one of those folks who have almost irritatingly clear memories of their own childhoods—clear enough to know that what I actually saw was often quite different from what I was told I was seeing—in my experience maturity is precisely the state of having both the language and the liberty to say what you see. As such, it’s a rarer and more precious thing than we think.

I'm suspicious of both contemplation and enchantment. Enchantment is a form of capture. If you are going to allow yourself to be captured, you must have complete trust in the magician. And they are a magician, after all. Why would you give complete trust to someone who has chosen to pursue that craft?

Contemplation is a form of waiting. Do not hunt the wren, but keep very still in the hope that if you are still enough a wren might land on your finger. And so it might. Or a pigeon might land on your head and do its business. Waiting is not a selective activity.

Perhaps I am just not trusting enough or patient enough, but I prefer accompaniment and surprise. I can't sit still and I won't submit to your enchantment, but I will go on a journey with you, as a friend, to unexpected and unexplored places. And I will keep my eyes open, accepting the scene before me as sufficient recompense for the labor of the journey, and yet willing to be surprised. For surprise is the great pleasure of a journey. It is surprise, not weary concentration, that changes how you see the world, not merely in that moment, but forever.

I am suspicious too of “truth, goodness, and beauty.” We live on Thulcandra, the silent planet, a world of lies, wickedness, and ugliness, with just enough of truth, goodness, and beauty showing through to make us melancholy or to drive us mad. That which seems all truth, goodness, and beauty may seek only to make us captive of a silver chair. The one thing this form of enchantment does not seem capable of is surprise. All that is false seems hung with a weary familiarity. But truth and beauty, goodness and joy, come always as a surprise.

When I get disaffected or exhausted with works of fiction, other than for the reason you cite, which I concur with, it is because I can see the author trying too hard to weave an enchantment with familiar and worn-out magic, or because they are trying too hard to force me into a state of contemplation by weary elaboration that sees every claw and feather but misses the Wren. Get on with it, I want to cry. Tell me a story. Surprise me if you can. But if you can't, that's okay, if you will at least stop fussing and tell me a story.

What I want from a book, then, is neither enchantment nor contemplation. I want to depart on a journey with an honest and amiable companion who does not try to dazzle me and does not make me wait, who is capable of enjoying with me the passing scene, and who is capable of leading me to places where, perhaps, though not necessarily, surprises may await.

"Haunted" -- a favorite for me as well-- jumped right to my mind when I read your interview comments. Katy, you seem to be able to hold so much more in your head in "one piece" than I can, and I can only scramble at little bits here and there. But what you said about enchantment as "a desirable readerly state; contemplation, a desirable writerly one" struck a chord with me. While any writer must first receive (being, language, ability, desire) in order to give (to plan, imagine, write), I wonder if the act of reception as a reader has a greater priority -- per CS Lewis in Exp in Criticism, which you likely know -- "The first demand any work of art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way. (There is no good asking first whether the work before you deserves such a surrender, for until you have surrendered you cannot possibly find out.)" The act of getting-out-of-the-way of a work that is worthy of such self-removal, this allows for the enchantment, which at this space, seems to be also a space of healing, of holding, of allowing the work to hold me as a reader in a space. On the other hand, I know if I feel enchanted or "held" by my own work (ha!) I am likely suffering from immense writerly blind spots, not creating a work that is enchanting; contemplating my work and its relationship with reality and the world, and how to sculpt it so that it conforms more closely to that seems more active, humble, productive, healthy. A random response, not encompassing your whole thought or all the articles you linked to (which look so good, ah, will return to them! And I also recognize too that all the words I'm using are so philosophically loaded and I've wielded them quite casually. (While taking a break from being on hold with doctors, etc!)