Perspectives (or the Series Formerly Known as 'Close Readings')

1. Real Presence, Richard Bausch

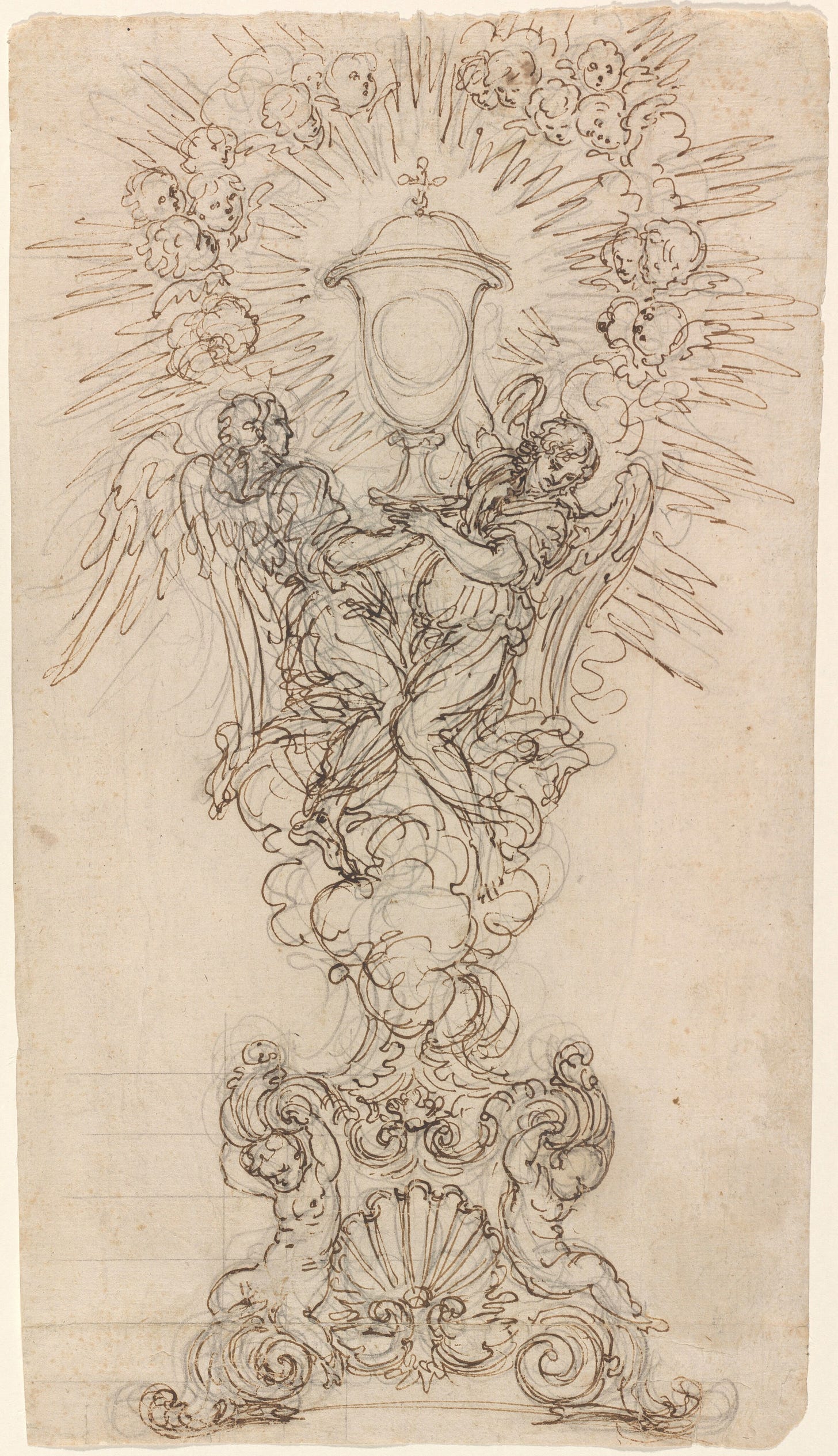

[Image: “A Monstrance with Two Angels Supporting a Chalice,” Giovanni Battista Foggini, courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund. Public domain.]

1. Skimmable or Skippable Prolegomena to This New Series

When I’m asked for existing examples of contemplative realism, so far I’ve tended to hesitate. No doubt it is a matter of my own fathomless obtuseness. But it strikes me that, as the history of ideas goes, this one coalesced only yesterday. So asking for a long list of its instantiations seems kind of like asking a newborn baby for triplicate copies of his résumé. Or, perhaps, am I expected to say—sounding like the person at the party by whom all the other attendees would least like to be cornered—“Never mind, know what? Here, you should read MY book!”

Come to think, given current norms of authorial self-promotion, I guess I am expected to say something like that. Lord have mercy.

Still, one would like to be less solipsistic. So, sure, it’s true that when I read both classic and contemporary fiction, I see plenty of precursors, or analogues, or resonances with the idea of contemplative realism. Several of them are listed in Joshua Hren’s Contemplative Realism itself, as gratefully acknowledged influences and teachers. But as yet, there can’t possibly be a lot of art that consciously aspires to contemplative realism as to an ideal. I do think there soon will be. Many of those writers are working; I’m fortunate to know some of them. But books happen slowly. So it’s going to be some years yet before there’s a real body of work here to discuss.

Meanwhile I’m extremely loath to ascribe motivations or aspirations to an author whose motivations and aspirations I can’t possibly know. Especially, I don’t want to assign someone else’s supposed aesthetic goals to them retroactively. I don’t want to map the present and future back onto the past, in a sort of solipsistic, revisionist, Hegelian move, like: ah! We have met the future, and it turns out always to have been going to be ME. Absurd. There have existed writers burdened with sufficient hubris to make this move. I’m not one of them. Nor, really, is anyone I know (in real time, rather than solely posthumously and through their writing).

That said, I think we can fairly say that certain works have anticipated, though maybe implicitly, this idea of contemplative realism. This series seeks to cover, close-read, and expand on some of those writers. Anyone I mention here will not be imperially claimed as a “contemplative realist” but simply, gratefully acknowledged as an influence. It’ll be someone from whom I have learned, maybe not everything they have to teach, but at least something vital to my own practice: something about how to frame, or how to follow up, the questions and mysteries I bring to my own work.

2. Moving On with the Series Formerly Known as “Close Reading”*

One of these writers is Richard Bausch,** whose story collection Living in the Weather of the World I reviewed in 2017 for Dappled Things. Though I’ll focus here on his 1980 Real Presence, I’ve also loved his award-winning Peace and the underrated Mr. Field’s Daughter, among others.

In Real Presence as in his other work, Bausch’s sentences unfold with a deceptive apparent slowness that is underwritten by a driving though subtle urgency. His visual pictures render a sense of fullness without overdetermination. Character matters to Bausch. So does sense of place. While he takes us through landscape and history, we are waiting for, and being taught to expect, event. From the first passage of Real Presence, expectation is palpable in the very teeth of stasis. The stage of the novel’s action will be

an outpost of sorts for the patchwork quilt of farm and forest one saw from the Shenandoahs, looking west. There had been no reason for it to expand because there were no coal mines nor any industry, and farms held most of the land.

Not far away from this patchwork idyll, however,

… a large tract of woodland … [had] signs up everywhere about what was forthcoming in terms of development. The signs were on telephone poles, fence posts, bridge abutments, trees, like the marks of sudden migration or a trail left by a passing army.

Through this landscape rattles the beater truck of the Bexley family: father, mother, and six children, the youngest of whom is unborn. They are dispossessed, disenfranchised, recently evicted, and seeking work. The Bexleys strike out and are turned away everywhere, until they come to the Catholic parish near Demera, which we are somewhat slyly told is “a place where nothing serious ever seemed to happen; people lived out their lives quietly and died quietly, and grieved the dead just as quietly.” Slyly—because in setting up this self-evidently flimsy expectation, Bausch invites us to get ready for what might (and will) happen if (when) we knock it down. The line is less an act of scene-setting than an invitation to the reader’s imagination to come out and play.

The line also challenges all the facile surmising that many urban readers*** will do about those rural communities, when viewed under the heading of “populations” and with a sociological/distancing rather than a personalist/magnifying lens. That is not the kind of viewing we are going to do here, Bausch wants to signal to us. We are going to see in a more first-order, more immediate, less “knowing” kind of way. We’re going to look under the hood of the rusty, rickety vehicle of prejudice we’ve possibly been unconsciously riding around within—prejudice about rural families living in poverty, as well as prejudice about isolated supercilious priests. (As well as who else? The novel has characters and concerns it hasn’t yet divulged to us, some of whose appearances will come as a true surprise.)

Anyway, seized by a fit of conscience, the parish’s pastor grudgingly jury-rigs the mendicant Bexleys a temporary shelter in the social hall. He lets them know he means the shelter to be occupied only until they find some better alternative. Again, that “only” is set up in order to be knocked down: the whole time the pastor knows, and the Bexleys know, and unless he is uncommonly sentimental about human nature the reader also knows, that it will likely take the displaced Bexleys months to find themselves resettled. Meanwhile Elizabeth, the mother, is in her third trimester, getting more swollen and disconsolate every moment.

The overtones are getting suspiciously Bethlehemic here, and it’s true that some of the religious thematics, at first introduction, risk feeling a bit on the nose: Msgr. Shepherd is the self-consciously refined, maybe a bit clericalist, pastor at St. Jude’s (patron of hopeless cases). He’s got a heart problem. His hillbilly deuteragonist—whose arc is crafted to reveal the ways both men have dodged self-giving love—is called by the moniker Duck. In a lesser writer’s hands these evident emblems of authorial concern could be played as meanspirited jokes, or wielded as idea-heavy bludgeons. Bausch finesses them.

And he does this largely by way of the reversal of expectations that those evoked symbols set up. If St. Jude’s turns out not to be so hopeless, if Duck learns not to duck, could it be that the evidently symbolic heart problem admits of cure? That a shepherd need not necessarily be a fleece-wearing wolf? Then, too, Bausch is evidently alive to, and skilled in the mimicry of, reality’s tendencies to be stranger than fiction, to furnish us with the counterexemplary and the confounding. A subplot of the novel involves a missing chalice, which begins as evidence of the misattunement and suspicion between Shepherd and the Bexleys, but ends as evidence of something entirely other—I won’t spoil it by saying what. Suffice here to say that Shepherd’s chalice serves us with a subtly spectacular example of the way a symbol can function on multiple levels at once, as well as the way small-m meaning within story can shift over time while capital-M Meaning, in its fullest sense, remains the same.

The Real Presence of the title is refreshingly unironic—this is a novel that, as its epigraphs about Hopkins and from Merton clearly declare, is written from and in and for belief in the Eucharistic Christ. Yet without discounting the importance of the metaphysical, Bausch has his characters and readers enter deeply into this particular belief’s many physical implications, corrolaries, and demands.

*Renamed to avoid possible confusion with the valuable and lively “Close Reads” podcast. I thought about calling the series “Scrutinies” before I remembered that this is already the name of a blog by the delightful and hilarious Dorian Speed, fellow fictionist and good friend.

**I learned about Bausch years ago by way of Amy Welborn’s always vibrant essays on fiction, in this case her piece on Bausch’s Vietnam-era Catholic novel Good Morning Mr. and Mrs. America and All The Ships At Sea. A couple of decades ago, Welborn edited a series of late-20th-c. Catholic fiction volumes called Loyola Classics, which is sadly now out of print but which ought to be hunted down in used copies by anyone at all interested in spiritual fiction of any kind. (Years ago I gave away a handful of mine and now sorely miss them; I still have Paul Horgan’s Things As They Are, which we’ll discuss later in this series.)

***Look, I’m an urban reader; I live in a city; I’m writing this in a comfortable air-conditioned room. I’m not trying to rag on urbanites. The need to not caricature cuts both ways, here.

I have to say that I don't really think contemplative realism has coalesced yet. Much as I have read about it and much as you and I have discussed it, it still seems to me like an amorphous cloud of ideas that has not yet coalesced. And the evidence of this is precisely the difficulty of saying whether a given work is contemplative realism or not.

I have read, and quite enjoyed As Earth Without Water, but if you asked me to point to what made it a work of contemplative realism, as opposed to any other modern literary novel, I would be at a loss. But let me suggest a project that might clarify things, at least for me, and perhaps for others. Let me suggest four works on a similar theme and ask you to compare them and say which is a work of contemplative realism and which is not, and to explain why. The four works I would propose are:

* As Earth Without Water

* Monk Dawson

* Mariette in Ecstasy

* In This House of Brede