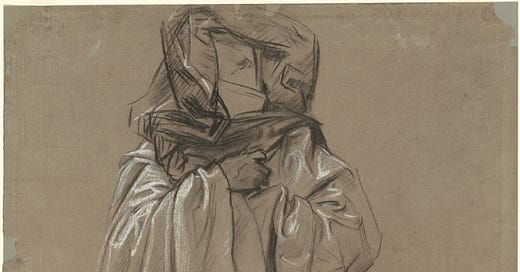

[Image: “Study of Ezekiel for Frieze of Prophets,” John Singer Sargent, 1890-92, courtesy National Gallery of Art (Corcoran Collection, gift of Miss Emily Sargent and Mrs. Francis Ormond, sisters of the artist). Public domain.]

NB: What follows is [the stub of] a review-essay [in progress] in response to Michael O’Brien’s fictional meditation By the Rivers of Babylon, which goes into greater detail about the technical problems of writing scriptural fiction than some of my agnostic readers may care for. If you’re skipping today’s post for reasons along these lines, I still hope you’ll hang in for the next one. Thanks for being here.

I wanted, with such warmth, to love this book. That, instead, I have such complicated perceptions and responses about it frustrates me at least as much as, I am sure, it will frustrate others. The outsider art of Michael O’Brien has been important, in ways I can’t briskly or facilely explain, to deep aspects of my spiritual life. Besides that, he is just an interesting figure. I don’t think you see anyone else, anywhere, that I’m aware of, doing quite what he’s doing as a self-consciously religious writer or receiving quite the same type of audience support for it. His doorstopping novels, which he produces with an astonishing regularity given their sheer length, are beloved by a certain stripe of Catholic reader. Their undeniable technical flaws are balanced by a lively interest, an inventive spirit, which certainly has to count for something. (…..)

[UPDATE: I’ve taken down an earlier draft of this piece, which, while I stand by the substance of its critiques, was relatively unpolished and underdeveloped. It felt urgent to get something said, but sometimes that sense of urgency is valid and sometimes it’s false. Two cheers for slow discernment, I guess. While I think about how to revise & extend, readers interested in learning more about O’Brien’s recent work can check out this recent review by Clemens Cavallin which gives a sense of his fiction’s characteristic tone and concerns.]

Well, if it is any help, I feel much as you do about O'Brien's fiction. It's a long time since I read it, so I cannot quote chapter and verse, but I remember it as lacking that particular grittiness that should mark a novel, the sense that its characters and events are wholly particular. Rather, I remember a sense that O'Brien's characters represented things, that they were archetypes performing archetypical actions.

It is perhaps the curse of anyone who set out to write "religious fiction" or "spiritual fiction" that they begin with the sense that they have SOMETHING IMPORTANT to say. And as long as that thought is in in their mind, they are not writing a novel, but something else in novel's clothing. The characters all stand for something and they tend to move from one pose to another rather than live the life they are living, because standing for something seems always to mean standing still. They exist only to strike the poses and the transition from one pose to another is not of sufficient interest to the author to make it convincing to the reader.

As you suggest, the SOMETHING IMPORTANT may be something some readers want to hear, and they may prefer to hear it in novel form, and there's nothing wrong with that, as long as the something important is true. But it is not a novel and it is not what a novel if for.

Christian morality is not complex. It's not even novel. It's just really really hard. So we are all either trying and failing, or not trying at all, and yet somehow troubled that we are not. And that is what novels should be about. The individuality of that struggle. Not the conception of it. Not being an exemplar for it. But a portrait of the blood and bone struggle of it. Because in the end the most comforting thing a novel can say is, "It's not just you."