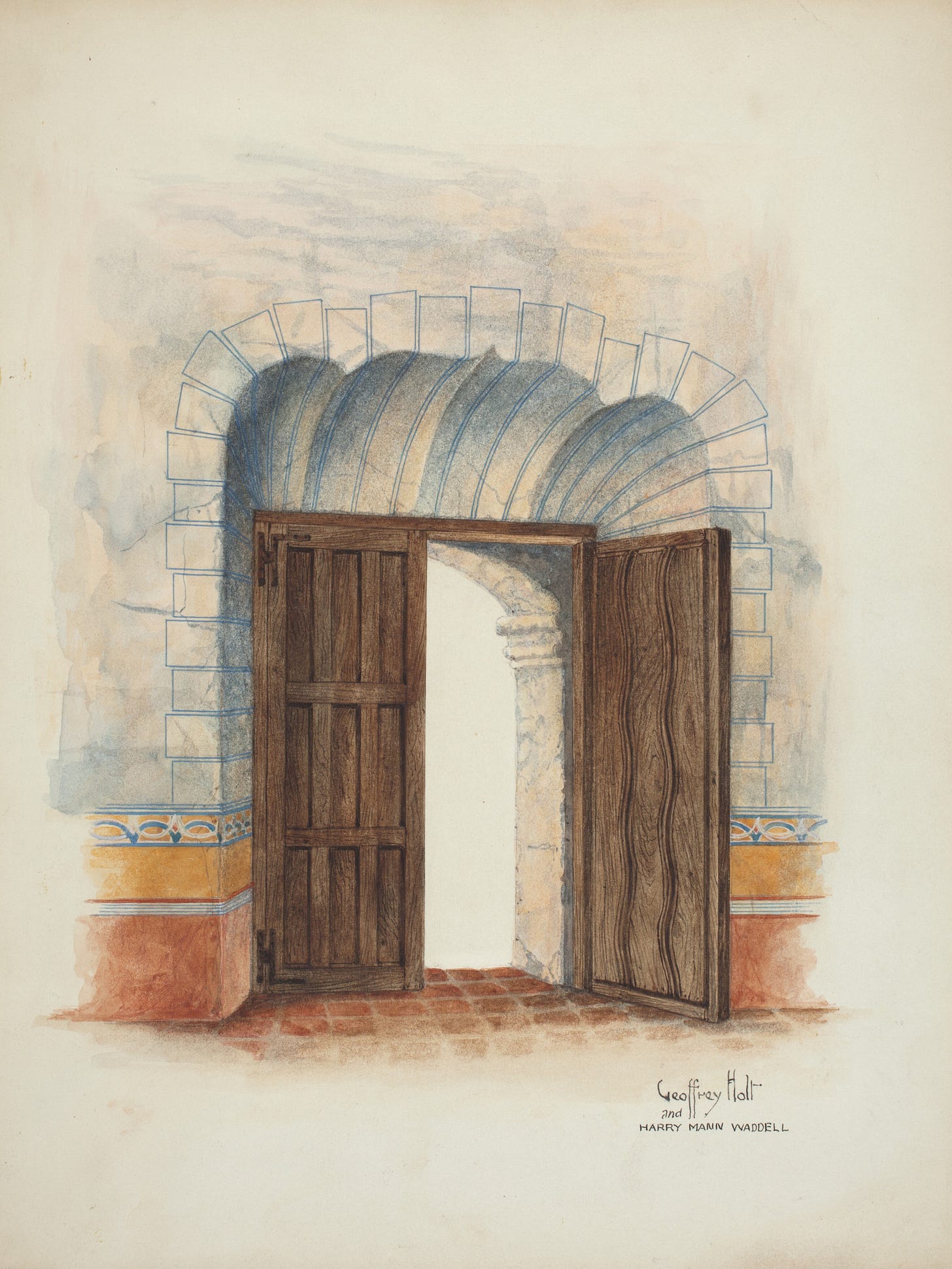

[Image: “Restoration of Interior,” 1935, Geoffrey Holt & Harry Mann Waddell, courtesy National Gallery of Art Open Access Collection, Index of American Design. Public domain. Title chosen for overt symbolism.]

Last week I went down to give a talk at lovely Ave Maria University; this is not the text of that talk, but rather an attempt to compress some of its core thoughts into a form that might be easier to get hold of. Because I was talking mainly to Catholics there, I got deeply into the weeds about Mauriac and the problems of the Catholic writer; here I seem to have a wider audience, so I’m going to leave my poor beloved recovering Jansenist for another time and just talk about the thing with wider appeal, which is the act of natural contemplation, or rather attention.

Expanding on the contemplative-realist observation that “not all moral vision is moralism,” I wanted to say that if fictional stories can be said to show us how to live, they most often do so not by showing us how to behave but by showing us how to observe. Action follows from love, and love follows from vision, and vision is a kind of plenitude of perception that we arrive at as a result of being open to receiving reality.

This openness has to be there first, before we can really pay attention to anything. Children own it naturally and lose it only slowly and under protest. Much of what adults must do in learning to “focus” in contemporary life as we’ve currently constructed it is learning to focus on relatively invested-with-meaning, but absolutely inessential, things. This process is not without its advantages, but its downside lies in how it can tend to shut down our original openness and warp our sense of perspective and proportion.

If we want to unlearn some of these bad habits, or at least soften our death-clutch on them, we could do worse than share acts of attention with artists and writers, who have trained themselves to pay attention to what they have come to believe are the right things in the right perspective and proportion, and who have considered reasons for these beliefs—which reasons, however, we will only have a chance of grasping if we loosen our control enough to follow along for a while with what they say and how they say it.

This is why it isn’t literary characters, or agents as we might do better to call them, who are most likely to open up new ways of seeing to us by showing us the way that they see. Rather, it’s the implied authors who (sub)create, voice, situate, present, and resolve the action of these characters, who do so. Characters are there to show not how people should act, but how people tend to act. But implied authors are there to show us how they pay attention, and there tends to be, if not an implicit ought in that showing, then at least an implicit I think this would be good for you, an implicit let’s share something worth sharing.

The distinction matters because if we want to avoid preachy, didactic art, we have to let characters behave as though they were real people, including making choices with which we disagree. Implied authors, dwelling within the real author, have to be different enough from the real author that they can buffer even some of the real author’s most deeply held beliefs and prevent forced, implausible, intrusive twists or unearned epiphanies. At the same time, implied authors tend to be aspirational, a way of being better than we really are, which is what Aristotle says is the thing we most tend to imitate in tragedy: people being better than they really are.

This seems counterintuitive, since in contemporary schema we tend to think of comedy as portraying the world better than it really is, tragedy worse. But the Poetics posits just the opposite. For Aristotle, comedy expresses our delight over the core goodness of things even though people can be kind of terrible; tragedy, our sorrow at the thought that no matter how good people are, and people can be glorious and godlike, they still can’t fix a kind of foundational brokenness in things.

But, comic or tragic, in modeling the act of paying attention—in imitating not just human action but human attention for our benefit—implied authors are showing us how to see not only various possibilities for how people may act but various possibilities about how to regard those options. We can still look for moments when characters bring, into their concrete circumstances, an abstract goodness we’ve been seeking to understand. Still, even in the majority of good stories, we’re unlikely to find any single character we can—or should—seek to imitate wholeheartedly, without holding back.

The same may not be true of life. We do eventually have to choose nonfictional exemplars for our action, if we won’t have fictional ones. And yet, often we still do this on the basis of story. Because for all of us, there are unqualifiedly true stories that we shape our lives around. We’ve been told these stories in a way that makes us treasure them; we may even have been told them in person, by real live humans, face to face, at the exact right time and in the exact right way for us to receive them. These stories could not have been told any other way. They would have lost some of their power by any other mode of telling. We know this in part because if we try to copy them to the page in what would seem to an untrained eye to be a totally natural way, they land as totally unnatural.

Still, we rightly persist in treasuring them. We found something in these moments we can’t quite put into words—something in someone’s eye or voice, something in the air, something in the angle of a bird’s feather or the glint of the sun off the window of a car—whose activity just then and there transformed us wholly. Made us different than we were before it happened.

Conveying this difference through writing—what makes it, what it consists in—let alone leading someone else to have such an experience through the quality of words you have put down on a page—is far from a simplistic matter. Don’t believe me? Try it sometime. You will find that it involves an experience not unrelated to what it is like to move house.

Forgive me if this analogy, or some version of it, isn’t original to me. And if there is a source and you know it—if you’ve encountered it elsewhere (Thoreau? Dickens?) and can remind me of something I may have read and forgotten—please let me know; I’ll happily acknowledge.

But the analogy is this: When you move house, you drag all your valued keepsakes and possessions out of their ordinary places and put them in one pile. No sooner is this done than you promptly realize that, to anyone but yourself, this pile of stuff now looks like exactly what it is: a pile of stuff. But there is real worth here. You know that. Still, the worth is not presented so as to meet the observer’s eye.

Well, the first draft of any piece of writing is the pile of your unmoved and unsorted stuff. And much of the art of writing consists in transferring to a new location, selecting, and (re)framing whatever in the pile may be of worth, in the hope that many observers—even if tired, even if distracted, even if traveling through some unknown valley of tears—can again live among the things you have presented, can gain some good from dwelling within that space of shared life with you and with what you value.

The question, then, becomes (for those of us who find this a good use of our time, this showing-forth of worth, not to be conflated or confused with gaudiness in a showing-forth of wealth or charm or superficial appeal): who do we have to be in order to perform this act of selection, this act of enframement? And not just one but many such acts, not just once but many times?

I will set that aside for now, without losing sight of it. Because from another perspective, that of the reader, we have also to ask: why should anyone trust a fiction writer, this evasive person who is apparently looking for someone better to be? Why aren’t we more suspicious (though perhaps some of us are already very suspicious) of the motives of such a person? At best—if we are canny enough to figure out that we can trust some narrative artists but should distrust others—on what basis do we or can we evaluate which ones are which, especially if we are set up by the mechanisms of culture to receive and react to all narrative artists, that is all possible narrators of direct experience, as though they were authority figures?

In some modes of education we are told, taught, prepared, to consider all direct narration of personal experience unquestionably authoritative. No doubt this can be a helpful corrective to certain kinds of abuse of authority (though it may, I’d submit, also lead to other kinds of abuse of authority). Viewed rightly, though, it can be a helpful corrective to a common cultural script by which people are made to believe that what has happened to them was of no importance, or that such events cannot be made into literature.

If it happened to you, or happened at all, it was of importance. If it happened to you, or happened at all, then it, or anything like it, it can be made into literature, though maybe not by you, at least not yet, not until you have put much careful thought into the way to tell it. Not the way your mother or your pastor or your department head wants you to tell it; not the way you think it needs to be told to become popular—unless perhaps your editor is right about this, as I can’t help but feel editors often are—but the way that best serves the reality at the story’s heart.

Every soul is of equal, immeasurable value. Therefore understanding the full truth about whatever shapes that soul is likewise of unquestionable value. The objective magnitude of the events doesn’t matter nearly as much as the mode and manner of the shaping the events have produced. At the same time, the magnitude doesn’t not matter, either. But it isn’t the thing most closely to be examined, in this context.

So that we may think well about all this, reality demands that we be able to face the plain question my own immensely patient editor once asked me—when I couldn’t stop myself from affixing the cart to the horse’s wrong end, trying too hard too far ahead of time to trace out the ongoing, self-perpetuating reverberations and ripple effects of my characters’ reactions to a key traumatic event, and their reactions to each other’s reactions—

—Okay. But what happened?

To become real authors reliable enough to shape trustworthy implied authors, we have to know: What has shaped our souls? And how?

This may be, at times it inevitably will be, different from the answer to the question of what has shaped our characters’ souls and how. We have to know our own business before we can attempt to know theirs. But if we sit with them and with ourselves long enough, in enough light, with enough acceptance of things as they are, they may lead us into self-knowledge. And self-knowledge, if we’re open to it, may lead us into the very truth we need to encounter.

*puzzle

Katy, I finally finished reading this. You’ve gotten so quickly to the heart of storytelling, and (I think) to one of the reasons why some stories “stick” and others don’t. I’ve been asking myself this a lot lately (would love to discuss with you on Friday), and I think this is an important piece of the pixie