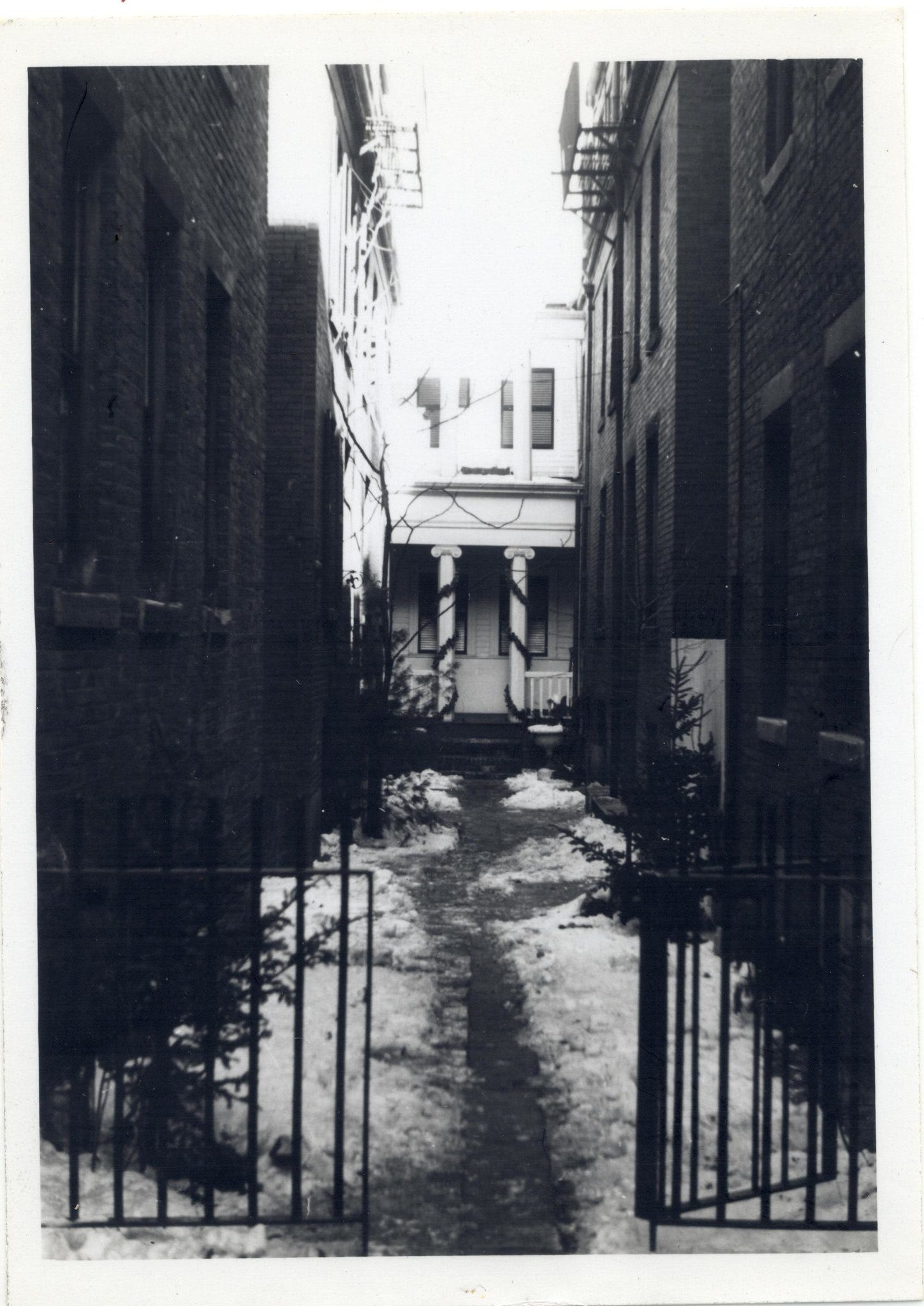

[Image: “Beacon Hill,” courtesy of Boston City Archives, used under Creative Commons 2.0 license.]

It’s been a while; let’s jump right in.*

For the rest of the summer Depth Perception will focus on a series of close readings of texts I consider influential on my own practice and understanding of contemplative realism, as a working fiction writer. I intend these to be more in the nature of appreciations than critical writings. And I’m considering them as practice for a longer series I’ve been planning, which will explore and unpack texts that are specially mentioned in the Contemplative Realism manifesto.

So today’s story is Fanny Howe’s “Radical Love,” from her short story collection Economics,** whose stories take place among Bostonians of the late twentieth century. Howe is one of those late-20th-c. writers we don’t discuss nearly as much as we ought to, especially within readerships of spiritually attuned fiction. One reason for this oversight may dwell in the fact that Howe is better known for her contributions to nonformalist poetry. Another may be that her fiction’s spiritual concern is so subtle: it more often turns up on the level of deep theme rather than overt content.

“Radical Love” makes an exception to that rule, as it deals openly with the intertwined questions of a believer’s life and of an unbeliever’s exploration into the mystery of that life. The story itself, in its nineteenth-century framing device, could clank around like the spare parts of an antique car in other, less nuanced hands, but in Howe’s it runs more than smoothly.

The kernel goes like this: A young, clever activist goes to a dinner party, where he listens to a slightly drunk professor telling him a story. The professor’s story is one of lost affection, ironic misattunement, and bewildering emotional loss: In his student days, a friend’s much younger teenage sister, Emily, fell in love with him. Though he did not reciprocate the romance he nurtured a friendship with her based on shared intellectual interests and observation of the world. Then one day, in a moment of near-transcendent bliss while walking home from a film, he promised to marry Emily when she was old enough and—in a phrase whose tongue-in-cheek spin coming from this mouth lands clearly enough with the reader, but flies over the head of its intended recipient—“all [his] sins were exhausted.”

Life intervened, and the professor broke his promise, adding to his litany of (implicit) sins: he married instead a woman closer to his own age, all the while keeping up a friendly correspondence with Emily. One day Emily came to visit and found the man who she believed was her fiancé already married to another woman.

Enraged, Emily placed a verbal curse on the couple—which we’re strongly encouraged to believe was efficacious, though the narrator himself almost can’t believe this. A cycle of failed relationships (for both) then began, spinning inward on itself ever more tightly like the whorl of a nautilus shell, and reaching its crisis point only when Emily and the narrator found themselves together again, on an icy day across a café table that looks like “life inside a mirror,” having the most definitive and conclusive conversation they will ever have.

I won’t spoil the content of this conversation for you. Here it is enough to say that the beast in the narrator’s jungle comes out to close ranks with him. Howe lands its leap as a genuine surprise. This once again evokes the narrator’s skepticism, and this expressed skepticism functions as a safe receptacle for the audience’s inclination to skepticism so that we, as readers, can consider the possibility that what Emily tells us she has experienced is real. Then Howe closes the story’s frame around the professor, painfully but not ungently, and leaves us dwelling with the different valences of insight each character has taken away from the experience according to each one’s capacity to receive. As readers we have to consider where we most identify—Howe doesn’t tell us which response to resonate with. She simply opens up what seem to be a range of reasonable possibilities for resonance.

The narrative is so incredibly tight, lean, fluidly moving, and yet contained within clean glinting surface, that if you’re thinking “this sounds Chekhovian,” you’re on the right track. Because its events take place among a certain kind of literary crowd, it lands as natural that the story comes right out and names Chekhov in its earliest lines of dialogue: which not only feels like a low-key acknowledgment of influence, but is brought out as such right away and then developed to a turn in the story’s astonishing last line (I won’t spoil it).

This is a bold move on Howe’s part. Anytime you openly name an influence, as a writer, you’re inviting comparison, and you’re heralding ambition: it’s quite possible this work doesn’t live up to that one, but I want to evoke it anyway, because it speaks of my aspiration, it gives you a clue to what I am trying to do. At times it may be a last-ditch gesture (on the writer’s part) of frustration—oh, I can’t, so just go read this other writer who did. But in this instance, I want to dare an opinion: Howe writes as Chekhov’s equal.

Accordingly, the achievement of the story has much to do with its matching of style to substance. To evoke a much different Russian writer, Howe’s “Radical Love” does what Bakhtin says Dostoyevsky asked all his narratives to do: namely

seeks the highest and most authoritative orientation … not as his own true thought, but as another authentic human being and his discourse. The image of the ideal human being or the image of Christ represents … the resolution of ideological quests. This image or this highest voice must crown the world of voices, must organize and subdue it.

And it does this within the tight compass of thirteen pages, most of which detail that paradigmatic human experience of failure to connect, an ill-starred love affair. Most astonishingly, it does it without the imposition of intellectual force. The “highest voice” gets into the story through the space Howe leaves open for it, not by means of logical proof. And that space in turn is created sometimes by judicious selection and suggestion, sometimes by implication and omission. The story makes Christ’s continued existence and relevance credible, in a context where skepticism about religion is the most salient social fact. But don’t just read it for its spiritual aikido; read it for the refinement of its style.

* Further housekeeping note, for those who desire it: These posts will continue to be sporadic through the summer and will return to a steady weekly rhythm in the fall. If you’re new (or haven’t opened a post for a while), welcome (back). I’m delighted you’re here.

** Could this volume, from Flood Editions, possibly be out of print? Seems you can at least find copies here: https://www.spdbooks.org/Products/097100594X/economics.aspx

The same title is also given to a collection of Howe’s novels, which I haven’t yet read but will have to pick up…